Malta’s Unjust Rent Laws

The Government of the Republic of Malta, a member state of the European Union, is unfairly targeting a small group of citizens by forcing them to rent out their properties at below market rates. Below is the opinion of the European Court in the Case of Buttigieg and Others v. Malta; Application No 22456/15 (http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-188275):

“The

Court has previously held that in a situation where the applicants’ predecessor

in title had, decades before, knowingly entered into a rent agreement with

relevant restrictions (specifically the inability to increase rent or to

terminate the lease), the applicants’ predecessor in title could not, at the

time, reasonably have had a clear idea of the extent of inflation in property

prices in the decades to follow.“

It also affirms that:

“Furthermore,

those applicants, who had inherited a property that had already been subject to

a lease, had not had the possibility to set the rent themselves (or to freely

terminate the agreement). It followed that they could not be said to have

waived any rights in that respect.

Accordingly,

the Court found that the rent-control regulations and their application in

those cases had constituted an interference with the applicants’ right (as landlords)

to use their property”

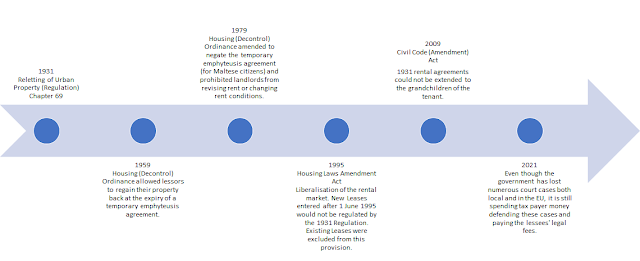

History

The 1931 law titled “Reletting of Urban

Property (Regulation) Chapter 69” was originally enacted to ensure a decent

supply of housing at reasonable prices since, at the time, it was common for

people to rent rather than purchase property. This was part of a drive to

ensure that the limited stock of vacant properties would not be left unoccupied

given the high demand. A Rent Board was

established and was given the right to seek out vacant properties and rent them

out. 1914 was chosen as a baseline for the setting of fair rent.

Many property owners were forced into

renting out their vacant properties because failure to do so would result in

them being reported to the Rent Board. It was common practice for persons to threaten

the owners of vacant properties to either sell or rent the property to them or

next of kin; less they report the owner to the Rent Board. Many people

reluctantly either sold the property or rented it out when threatened with such

action.

The Second World War came and went and the

country’s economy and social well-being started improving. The governments of the time did their part to

increase the stock of social housing and a number of ordinances related to the

1931 law were issued. The 1959 Housing (Decontrol) Ordinance was one that

allowed lessors to regain their property back at the expiry of a temporary

emphyteusis agreement. This became the type of rental contract lessors started

enacting with lessees. All parties were clearly aware that on expiry of the

agreed time-frame the property would revert to the landlord.

The spanner in the wheel was thrown by the

1979 Ordinance that technically nullified the expiry clause of pre-agreed

contracts if the lessee was a Maltese national. With this ordinance the lessee

could not be evicted and landlords were severely restricted in their ability to

adjust rents or conditions in the rental agreements that were never intended to

not have a termination. One grievance was the fact that it became possible for

relatives of the lessee to inherit the rent with identical conditions to the

lessee who had preceded them.

In 1995, the government passed legislation

to liberalize the rental market. Rather than enact legislation in which all

lessors would be treated equally, it only liberalized new contracts entered

into after 1st June 1995. For

new leases after June 1995, the parties were able to negotiate market price

rates, have a predefined rental duration, have clauses that prohibited

subletting and could include clauses to adjust rates. Pre-1995 had none of

this; the properties still earned rent established years before, and had no

protection against subletting or the automatic transfer to relations of the

original lessor at the same rent as those who had been occupying the property

before them.

In 2009 a revision extended the same 1931

conditions so that they would not extend to the grandchildren of the original

tenant, yet it did not address properties that had already passed to the

grandchildren. This legislation means that there are current property owners

who will not be able to take ownership of their property before the next

century. Today there exist property

owners who have never been able to access such properties and some never will

during their lifetime.

Why is the Maltese Rental unjust?

The 1995 legislation created an anomaly

because it differentiated between pre and post 1995 lessors; clearly favouring

the latter while burdening the former with responsibilities that should be

carried by society as a whole and not by a targeted group of people.

It also differentiated between lessees.

Lessees in pre-1995 rents clearly benefited over those who had to pay market

rates. The extent of unfair benefits to pre-1995 lessees was further aggravated

because siblings, children and grandchildren inherited benefits not afforded to

other lessees who would take a [post-1995] lease contemporaneously.

Another legal bias against landlords was an

ordinance which nullified a pre-agreed temporary emphyteusis. For all intents

and purposes, it was a dictator-style law that completely disregarded any plans

and aspirations landlords might have had for their property after the

contracted termination of the lease.

Landlords are the victims

From appeal No 22/19 GM (Joseph Grima,

Georgina Grima, u Doreen Grima v. L-Avukat Ġenerali u Lawrence Aquilina u Iris

Aquilina) a property valued at Euro 275,000

by a court appointed architect was earning the landlords Euro 205 per

annum because rent could not be adjusted. Furthermore, this amount is taxed,

meaning that the net earnings for the landlords is even less.

While receiving a pittance for such

properties, any person who inherited such a property would pay property

inheritance tax on the property’s current valuation and based on the assumption

that it is vacated.

All structural repairs must be borne by

landlords. The law allows an increase of 6% on base rent. For a baseline rent

of Euro 185 this would amount to Euro 11.10. Many do not justify the legal and

architectural fees necessary to process this request and end up simply carrying

the costs themselves without passing them on to the lessee. On properties that

are so old, maintenance costs are frequent and extremely costly because of the

materials and construction techniques used at the time. One such expense could

easily wipe 25 years of rent.

Landlords impacted by pre-1995 legislation

are not Malta’s version of Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk. They are people who, in

their absolute majority, fall into the low and middle-income tier. Many of them

acquired or inherited the properties that were originally purchased decades

ago. As can be seen in the chart, the price of real estate was a fraction of

what it currently retails at. These are people who live an average lifestyle

and whose children had to take mortgages or pay commercial rent rates for their

own habitation. These are people who may have a small seaside property but are

unable to use it for their own enjoyment.

If they need additional income, they cannot

rely on the market value of the property because, with tenants paying rent that

is a fraction of the true market value, this is very low. The equity of any

property with an incumbent that cannot be evicted and who is paying unrealistically low rates is as low as

it can get. There have been cases, many undocumented, in which landlords were

forced into selling such properties at dirt cheap prices when they are in dire

straits, such as requiring money to help out their children, cover medical

expenses, fund a project or to cover costs related to the property itself

(paying inheritance tax or paying for structural repairs). There have been many

stories of tenants who would squeeze the price to ridiculous prices when they

would realise that the landlord is in a bind and that they practically hold all

the negotiation cards. Aging landlords whose source of income is, for example,

a pension, do not have the financial, physical and mental strength to battle

incumbent tenants. There are no official documents that describe these events

because, from a legal perspective, the contract was voluntary and does not document

the justification as to why something is sold at a ridiculous price.

The right way to govern

The government should not see the pre-1995

landlords as enemies. It should not attempt to drive public opinion against

them and should not tell tenants in such properties that when some of these

landlords try to seek legal remedy it will carry their legal costs and will, as

has happened, end up assuming liability for any penalties imposed by local and

European courts.

The government should stop trying to sell

the story that those currently occupying the properties are victims; for

starters a proportion of them are not the original tenants; they simply

inherited a good thing at the detriment of other members of society and are

simply riding this unjust wave. Secondly

since 1995 (and in many cases much longer than that) these tenants, like almost

every other member of society, should have made plans, and through hard work

and sacrifice planned their future rather than relied on a government leeching

other members of the same society. Thirdly lessees that had a contractual end

of lease are the victims of legislation that, as has been deemed in many legal

challenges, is abusive.

The way the government attempts to justify its behaviour (and make property owners look bad) is to project tenants as being “frail little old widows”. While it is not universally true, in 1959, 1979 and 1995 many of these would have been virulent spring chickens. If the government truly respects all members making up the Maltese society it should develop projects funded through taxation, rather than abuse a subset of society and target it to, single-handedly, do its work.

Conclusion

It is clear that the Maltese government has

no intention of lifting a finger to right this injustice. Landlords caught up

in this conundrum need to stand up to fight for their rights. Those who have

the resources should challenge in the various courts. Irrespective of

resources, an association to represent lessors’ needs to be set up and

supported. This organisation will be able to look at the options that can be

taken, direct coordinated campaigns and push the cause at the European level.

It is appropriate to conclude with the

Article 1 of Protocol No 1 of the European Court of Human Rights (https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Guide_Art_1_Protocol_1_ENG.pdf).

This has article has been referenced in many Maltese rent related court cases:

“Every natural or legal

person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall

be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the

conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international

law.”

Comments

Post a Comment